PARIS: BENEATH THE ROMANCE, THE BONES

Paris—La Ville Lumière, the City of Light—is famed for its romantic strolls along the Seine, lazy afternoons at sidewalk cafés, elegant facades, timeless history, and, of course, the ever-graceful Eiffel Tower. But beneath this vibrant, glimmering metropolis lies a shadowed underworld—a chilling subterranean labyrinth filled with the skeletal remains of its own citizens.

Welcome to the Paris Catacombs: an expansive network of ancient quarries, winding tunnels, and bone-lined passageways that cradle the dead in the quiet dark.

My last memory of Paris was from 1994, when I was just seven years old—too young to appreciate much beyond the glint of souvenirs and the sugar rush of pastries. But now, armed with a deep fascination for the macabre, I returned two decades later with a very different mission.

When my family decided to tour Europe in 2014, with Paris on the itinerary, I saw my golden chance. I dove headfirst into research—and that’s when I discovered the Catacombs.

By the 17th century, as Paris blossomed into a thriving European capital, it faced a grim and pressing dilemma: its cemeteries were overflowing. Improper burials, open graves, and unearthed corpses were becoming disturbingly common. Les Innocents, the city’s oldest and largest cemetery, became a symbol of this festering problem. Residents of the surrounding area began to complain about the unbearable stench of decaying flesh and the spread of disease wafting from the burial grounds.

In 1763, Louis XV issued an injunction banning all burials within city limits. But the Church, reluctant to disturb sacred grounds, resisted the order—and for nearly two decades, nothing changed.

That is, until disaster struck.

In 1780, after weeks of relentless rain, a wall surrounding Les Innocents gave way—spilling decomposing bodies into neighboring properties. It was a wake-up call that the authorities could no longer ignore.

On 9 November 1785, the Council of State ruled that Les Innocents would be closed, emptied, and converted into a public market—the site we now know as Forum des Halles. Following this, Monseigneur Leclerc de Juigné, Archbishop of Paris, issued a formal decree ordering the removal of the cemetery’s contents.

Now came the pressing question: where do you relocate millions of bodies?

The answer lay beneath their feet.

The city chose to repurpose the disused limestone quarries of the Montrouge Plain, known as the quarries of Tombe-Issoire, located on the outskirts of Paris. These quarries, dating back to Gallo-Roman times, had long provided the stone that built Paris’s grand architecture. Now, they would serve a darker, quieter purpose: to house the dead.

On 7 April 1786, the quarries were sanctified in the presence of Abbots Mottret, Maillet, and Asseline. The process of transferring the bones was highly ritualized: always at nightfall, the carts—shrouded in black cloth—moved silently through the streets, followed by priests chanting the Office of the Dead. The first transfer, involving the remains of over two million Parisians from Les Innocents, lasted fifteen months.

Between 1792 and 1814, sixteen other cemeteries across the city were emptied. During the French Revolution, Parisians began interring their dead directly into the ossuaries below.

Some notable figures who now rest in the Catacombs include revolutionary firebrand Jean-Paul Marat, beloved writers François Rabelais, Jean de La Fontaine, and Charles Perrault, sculptor François Girardon, painter Simon Vouet, and architects Salomon de Brosse, Claude Perrault, and Jules Hardouin-Mansart.

Later, between 1859 and 1860, the ossuary was expanded again to accommodate bones discovered in long-forgotten cemeteries during Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s dramatic redesign of Paris. The work was completed in 1860, and by 1867, the Catacombs were opened to the public.

Today, only two kilometers of the network are accessible to visitors—but beneath Paris, the tunnels stretch an astonishing 300 kilometers. A city of the dead, hidden beneath the living.

We started our day early on Thursday, 11th December 2014—waking at around 7:30 a.m. and stepping out of our Airbnb apartment just an hour later. We were staying at 3 Rue de Buenos Ayres, Paris—an incredibly convenient location, just a minute’s walk from the Eiffel Tower and the nearest RER lines.

For those unfamiliar, the Paris RER (Réseau Express Régional) is a network of five express train lines that link the city center to its surrounding suburbs. Within Paris, the RER functions like a high-speed metro, while beyond the city limits, it serves as a commuter rail—connecting key destinations like Charles de Gaulle Airport (RER B), Disneyland Paris (RER A), and Versailles (RER C) to the city’s heart.

We began our journey at Champ de Mars – Tour Eiffel station and boarded the RER C line heading toward Saint-Michel – Notre-Dame. From there, we transferred to the RER B and rode it to our final stop: Denfert-Rochereau—the gateway to the Catacombs.

Upon exiting the metro station, we paused for a moment to get our bearings and locate the entrance to the Catacombs. There was a directional sign pointing straight ahead—but beyond it stood nothing more than a row of neatly lined old buildings. No dark arches. No spooky gates. No ominous stone staircases. Just... quaint Parisian façades.

By this point, I was starting to feel a little anxious. If we were lost, I was definitely going to be in trouble. I told my parents to wait while my brother and I crossed the street to investigate. If the sign said it was here—it had to be here somewhere, right?

Thankfully, as we got closer to one of the solid green buildings, we spotted a modest sign hanging beside a small, unassuming door. It confirmed what we hoped: this was the entrance to the Catacombs.

Phew. Crisis averted.

We arrived about half an hour before opening, so we decided to take a quick stroll around the neighborhood to pass the time. We couldn't have been gone more than ten minutes—but by the time we returned, a short line had already formed outside the entrance. Not wanting to end up stuck at the back, we quickly joined the queue. I was practically vibrating with excitement.

Soon, the entrance door creaked open, and a young staff member ushered us inside. We stepped into a small room where the ticket booth sat at the far end, tucked beneath low ceilings and a faint hum of underground silence.

Tickets to the Catacombs and the accompanying exhibition were €12 per person, or €16 for a combo ticket that included entry to the Archaeological Crypt beneath Saint-Michel – Notre-Dame. Audio guides were available for €5, in French, English, Spanish, and German.

“Quatre billets, s'il vous plaît!” With my ticket in one hand and camera in the other, I was all set to dive into the depths of the Catacombs of Paris.

We descended 130 steps down a tight, spiraling stairwell that felt like a passage into another world. At the bottom, we arrived in a small, dimly lit room that hosted a photography exposition tied to the ossuary. We lingered there briefly—barely a minute or two—before continuing into the unknown.

The tunnel ahead narrowed, flanked by ancient limestone walls and lit only by sparse, flickering lamps that cast long, shifting shadows. As we ventured deeper, the air grew noticeably colder. A soft chill crept across our skin—subtle at first, then constant—as the underground dampness settled around us like a second layer of clothing.

Before entering the Ossuary proper, the path led us through a lower-level corridor—a short detour that offered a quiet but striking introduction to the artistry buried deep beneath Paris. Here, we encountered a series of intricate stone sculptures, dating back to the earliest known works in the Catacombs. These were the creations of Décure, known as Beauséjour—a former soldier in Louis XV’s army, who later became a quarryman under the Quarry Inspection Unit.

The first of Décure’s sculptural works depict scenes from the Cazerne district, including a detailed representation of the former L'Hôpital des Anglais, where he had once been billeted during his military service. Carved painstakingly by hand into the limestone, these pieces are a haunting fusion of memory, labor, and reverence—fragments of one man’s past etched into the very bones of Paris.

But Décure’s devotion to this subterranean world came at a cost.

While working on an ambitious personal project—a secret staircase that would connect his sculptures to the surface—Décure was tragically injured in a rockfall accident. He never recovered from his wounds. The staircase was never completed.

And so, Décure’s legacy remains hidden in the shadows: a soldier-turned-sculptor, who traded the light of the world above for the cold embrace of stone, and left behind silent monuments that still whisper of his presence centuries later.

The path finally led us to a narrow stone opening—the true threshold of the Ossuary. We were now standing 14.34 meters below the surface, deep beneath the streets of Paris.

Etched above the entrance vestibule was the chilling verse penned by poet and Abbot Jacques Delille, a grim greeting to all who pass beyond:

“Arrête! C’est ici l’empire de la Mort.”

(Halt! This is the empire of Death.)

A shiver ran down my spine. This wasn’t just a clever inscription—it was a warning. A promise. A sacred line that separated the world of the living from the kingdom of the dead.

Just beneath the archway stood a stele commemorating the official creation of the Catacombs. This monument had originally been placed at the first entrance of the Ossuary, but was later moved to the current vestibule following the extension of the tunnels.

It felt like stepping into a temple—not one of marble and stained glass, but of bone, shadow, and silence.

Upon entering the Ossuary, I immediately noticed something that set it apart from the other bone-filled sanctuaries I’d visited. Unlike the enclosed exhibits at Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini in Rome, the bones here in the Paris Catacombs were completely exposed. No glass panels. No fences. No protective barriers between us and them.

I could stand mere inches away—close enough to trace the contours of a skull with my eyes, to see the fine cracks and weathered hollows carved by centuries of stillness. The air was cold and damp, heavy with the scent of ancient stone and lingering decay. Every breath tasted faintly of mineral and time.

A hush blanketed the tunnel, broken only by the soft shuffle of footsteps and the occasional drip of moisture echoing through the passageways. It was quiet—not the kind of quiet you find in a library, but a deeper silence, one that pressed against your ears like a held breath.

It felt at once intimate, unsettling, and oddly reverent—as if the dead were not just remembered here, but watching.

The path we followed wound its way between two towering walls of bones—rows upon rows, mostly composed of tibias and femurs, stacked with eerie precision. The arrangement was almost architectural, as though we were walking through a cathedral sculpted not of stone, but of mortality itself.

Adorning these walls were cranium-studded friezes, where skulls had been carefully embedded in decorative patterns—protruding like silent sentinels, breaking the smooth symmetry of the walls. They added a strangely romantic, almost reverent elegance to the macabre design, as if death itself had been made ornamental.

It was grotesque… and beautiful. A paradox sculpted in bone.

At this point, the tunnel widened considerably, giving us a bit more breathing room—but the ceiling remained oppressively low. There were moments when I could feel the rough stone mere centimeters from my scalp, as if the earth itself was leaning in to listen.

As we ventured further into the Catacombs, we began to notice numerous secondary tunnels branching off in all directions, each one swallowed by untouched darkness. Though sealed off to the public, these shadowy corridors hinted at the true scale of this ancient labyrinth—a vast, skeletal underworld stretching for hundreds of kilometers beneath the city.

They were paths not meant to be taken. But their silent presence whispered to the imagination, suggesting stories and secrets buried deep within the veins of Paris itself.

Below is an image of one of the oldest arrangements in the Catacombs—a chamber steeped in silence and symbolism. The room is flanked by two imposing black-and-white pillars, which frame and enhance the presence of the lampe sépulcrale (sepulchral lamp) positioned prominently at its center.

This modest yet powerful monument was built to replace an earlier version of the lamp—one that once held a continuous flame, burning steadily to maintain air circulation throughout the galleries. Though the fire no longer burns, its purpose—and the memory of its glow—lingers, a quiet reminder of how even in the kingdom of the dead, life still needed to breathe.

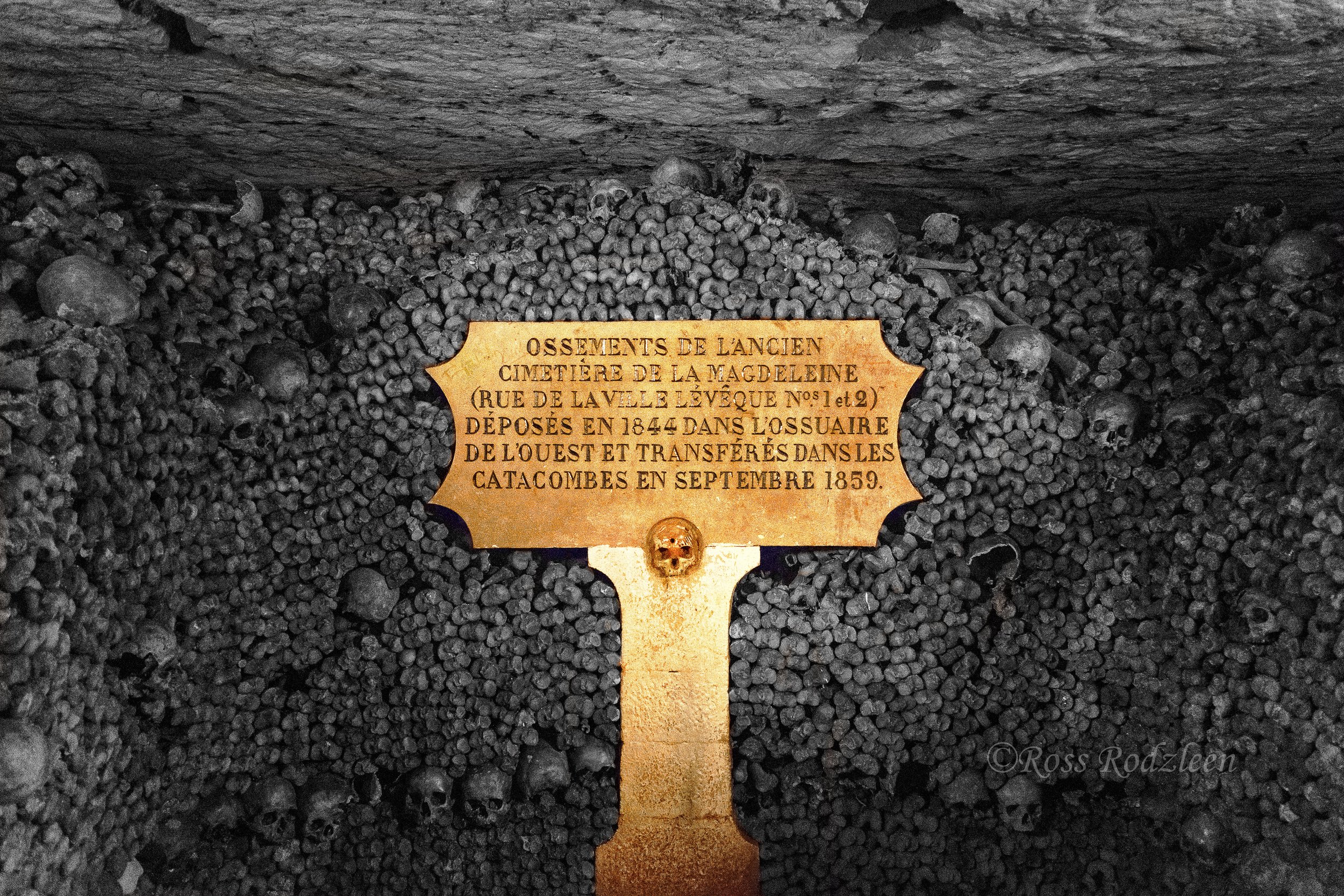

This sign narrates the journey of remains from the Madeleine Cemetery, specifically those that arrived at the Ossuary in 1859. Before reaching their final resting place within the Tombe-Issoire quarries, the bones were first transferred in 1844 through the Ossuary of the West, also known as Vaugirard Cemetery.

What makes this particular transfer especially haunting is its royal and revolutionary history—did you know that numerous guillotine victims from the French Revolution, including King Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, were originally buried at Madeleine Cemetery?

Now, their remains lie deep beneath the streets of Paris—no longer beneath palace ceilings or public scaffolds, but among the anonymous dead, cradled in the eternal silence of stone.

The 1859 bone deposit was made famous by the self-portrait taken by Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, a French photographer, caricaturist, journalist, novelist, and balloonist, who produced the first underground photographic reportage in the Catacombs. This was made possible thanks to the invention of electric light. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

In the French Revolution Crypt stood three monuments, each recalling three separate events associated with the period of social and political upheaval in France.

The first occurred after the resignation of the Minister of Finance Loménie de Brienne which sparked violent combats on 28 and 29 August 1788 on Place de Grève (Place de l'Hôtel de Ville). Victims of this ordeal were later buried in the Ossuary.

The second monument cites the Réveillon riots which broke out when the owner of the Réveillon wallpaper manufacture, Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, allegedly declared that a worker could survive on fifteen pennies a day. The statement provoked his employees to rebel and on 28 April 1789, the factory was ransacked and torched.

The third monument marks the attack on the Tuileries, the official residence of Louis XVI after the people of Paris marched on Versailles in October 1789. On 10th August 1792, 900 Swiss guards were brutally killed, many tortured, mutilated and decapitated while defending the Palace.

We had now reached the section housing the bones from the Saint-Laurent Church. This spot contains the only monument in the Ossuary that references the 1871 Paris Commune (Commune de Paris)—the first successful workers’ revolution, which existed from 26 March to 30 May 1871.

If you look closely, you’ll notice something curious: the inscription on this monument has been chiselled anew. The original verse read “violées par les Fédérés” (violated by the Communards)—a politically charged accusation against the revolutionaries. But that line was later removed and replaced with a more neutral term: “Déposés” (laid to rest).

It’s a small change—but one that speaks volumes about how memory is shaped, rewritten, and softened over time.

Deeper into the Ossuary, within the Crypt of the Passion, stood one of the most remarkable sights of all: a monument known as "The Barrel." Here, bones had been meticulously arranged around a central steel pillar, forming a massive circular structure resembling a giant vat or cask. It's equal parts sculpture and reliquary, macabre and mesmerizing.

This crypt also holds one of the most whispered secrets in the history of the Catacombs. On the night of 2 April 1897, between midnight and 2 a.m., a clandestine concert was held here, far beneath the Parisian moonlight. It wasn’t just a musical performance—it was an act of transgression, reverence, and thrill-seeking audacity.

Roughly a hundred patrons descended into the Catacombs under the cover of night. Some were artists. Others were aristocrats. A few were simply curious Parisians chasing the thrill of something forbidden. The audience gathered in hushed clusters within the Crypt of the Passion, their shadows dancing against the walls, cast by the dim, flickering glow of gas lanterns and candles smuggled down in canvas sacks.

Musicians set up just beside The Barrel, that strange, monumental vat of bone. It towered beside them, a silent audience of its own—watching, listening. The instruments played on, their notes rich and strange in the acoustics of the stone chamber. The violin’s wail, the haunting reverberation of a cello, the soft tremor of piano keys transported the audience into a surreal communion between life and death.

Every note seemed to reawaken the silence, to stir something ancient within the walls. You could almost imagine the skulls turning their hollow gazes toward the music, as if they, too, were listening—remembering.

Was it a tribute? A dare? A poetic act of rebellion? Perhaps all three.

Eventually, the concert ended. The crowd dispersed as quietly as it had gathered. No official record was ever made. No permission ever granted. But the story lingers—a myth in the marrow of the Catacombs, proof that even in a city of bones, music could still rise and move the soul.

Just a few meters ahead, the journey through the ossuary neared its end. Above the exit door, a final inscription caught my eye—simple, solemn, and deeply fitting:

"Memoriae Majorum"

("In memory of our ancestors").

It was a phrase that perfectly encapsulated the religious reverence and macabre beauty with which this entire space had been conceived—a reminder that these bones were not just relics of death, but testaments to lives once lived.

After spending forty-five surreal minutes underground, we ascended the final flight of narrow, spiraling stairs—each step drawing us closer to daylight, warmth, and the hum of the world above.

At last, we emerged—back into the city of light.

But something lingered. A hush. A weight. A deeper understanding of history, mortality, and the strange, sacred poetry of the Paris Catacombs.

Before leaving the area, I made a quick stop at the Catacombs gift shop, located right at the exit. And yes—I treated myself to a surprisingly adorable Catacombs throw pillow. (Because nothing says souvenir from the Empire of Death like a cozy little cushion!)

I have to admit, though—I was relieved to be back on the surface. As much as I loved every moment of the tour, the low ceilings and tight passageways were starting to press in on me, and a hint of claustrophobia had begun to settle in. Still, as I mentioned in my post on the Sedlec Ossuary, death has a way of reminding us to live more fully. To appreciate breath, sunlight, movement—the preciousness of being alive.

That said, I couldn’t help but feel a quiet discomfort at the thought of this open-air presentation of human remains. While many visitors are respectful, some of the bones had been defaced with graffiti, which felt like a violation—a disruption of the sacredness intended for this space. These were people, after all. Once loved, once living.

But despite those uneasy thoughts, I’m truly glad I made the decision to visit this morbid masterpiece. So much so, in fact, that I returned a year later—drawn once more to the silent poetry of stone and bone. During that second descent, the tour followed a slightly different route, offering new perspectives on a place that never quite feels the same twice.

This is the only skull with a full set of lower teeth! A rare dental celebrity in the kingdom of the dead.

I’ll definitely be visiting the Catacombs again the next time I’m in Paris. I can only hope that more tunnels will be opened to the public in the future—just imagine what secrets might be lurking in the shadows of those untouched passageways...

If you're curious (or courageous) enough to embark on this morbid yet profoundly eye-opening tour, you can find more details on their official website [insert link here].

Merci pour votre lecture!

Until the next descent... 🖤💀